The recent case of PN, who was blocked from boarding her flight back to the UK after being unlawfully deported, shines a light on the long standing, contradictory, and hypocritical relationship between the UK and Uganda over homosexuality. In this historical tragedy, the LGBTQI+ community have suffered as pawns in a game of law.

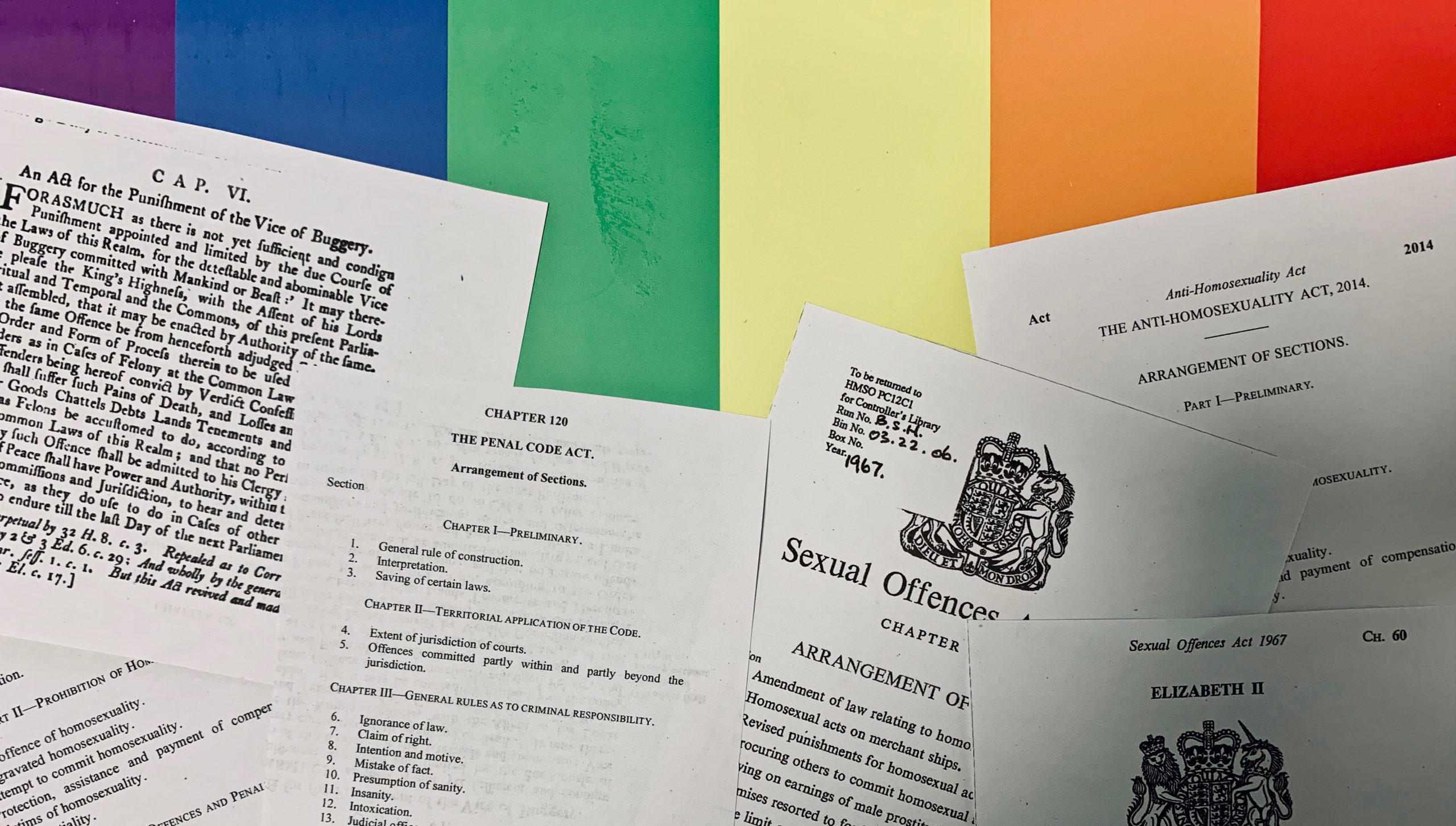

It started long ago, in 1533, with Britain’s Buggery Act. This Act, part of the centralising legal reforms of King Henry VIII, enshrined the state illegality of homosexual sex, and made it punishable by execution. Sapphic, or lesbian, sex was not criminalised, not because it was accepted, but because it was largely denied or ignored. In legal terms, women were not considered as agents, for example, married women’s legal personality was subsumed under their husband’s legal status as “two souls in one flesh.” In 1828, the Offences Against the Person Act modernised the 1533 law, in 1861 the penalty was reduced from death to imprisonment, and in 1885 the Criminal Law Amendment Act set the punishment at two years’ imprisonment, however widened the net to include any homosexual act witnesses or not.

Unsurprisingly, the country so threatened by same-sex love that they had to punish it, was the same country that felt so insecure in its status that it had to violently subjugate other countries in order to feel big and powerful.

So, whilst at home, the British were tinkering about with how best to punish men for expressing their affection for other men, abroad, they were tinkering about on other people’s land and claiming it as their own. Privileged British men with guns started stomping around the land that was to become Uganda in 1870s. Identifying as straight, entitled and superior, first Sir Samuel Baker, then General Gordon, and ultimately Captain Lugard, had their eyes on the three kingdoms inhabited the area of today’s Uganda: Buganda, Ankole and Bunyoro. However, contrary to the homophobic views that dominated Britain, in East Africa, opinions on same-sexuality appear to have been accepting. King Mwanga II of Buganda for example, was openly bisexual, and among the Lango people, certain men, named mudoko dako, were treated by society kindly as women, and believed to form a “third gender” alongside male and female. Nevertheless, this acceptance was soon to end. In acts that were the anitthesis of respectful, by January 1892, Captain Lugard managed to force Mwanga to sign a treaty recognising the British East Africa Company’s authority in Buganda. The British Government’s official Protectorate of Uganda began on August 1894.

What followed was a brutal and unashamed campaign to control the people of Uganda and impose British customs and law. Of course, what was law in Britain was deemed appropriate to be the basis of law everywhere, and laws prohibiting same-sex sexual acts were enacted under British colonial rule. The colonial period, stretching into the mid 20th century brought with it immense legally sanctioned degradation of subjugated peoples shattering previously existing communities. In 1950, in a brutal culmination of state sanctioned homophobia, a new Penal Code was enacted, enshrining the prejudices of their British overlords clearly in Ugandan law. Section 145: Unnatural offences; Section 146: Attempt to commit unnatural offences, and Section 148: Indecent practices, outlawed homosexual sex. As women in Ugandan law got the same disregard from the colonialists as in British law, the act only applied to men.

As anti-homosexual legislation was passed in Uganda, in a cruel twist of fate, back in Britain, the 1950s public mood was beginning to be more empathetic and accepting of lesbian and gay people. Alan Turing, the Bletchley Park scientist who broke the enigma code, was convicted of gross indecency in 1952, and was found dead in 1953. Convictions of the beloved actor Sir John Gielgud and a Peer in the House of Lords, in the same year, served to turn the public mood against criminalisation. The Government asked Sir John Wolfenden to investigate homosexuality and prostitution. The subsequent 1957 Wolfenden report, concluded that homosexuality, in limited circumstances, should be decriminalised. Ten years later, in 1967, the Sexual Offences Act became law, making sex between two consenting men over the age of 21 in private legal.

Meanwhile, Uganda had their own triumph, winning self-government on 1st March 1962. Yet lesbian and gay rights were not on their mind. From 1966, dictatorship marred and weakened the legislative function. First under Milton Obote, then after the military coup in January 1971 by Idi Amin, the order of the day was more, rather than less, discrimination. Ugandan Asians were exiled from the country and hundreds of thousands of politicians, journalists and intellectuals were killed.

President Museveni, sworn in as president in 1986 and still in power, has not halted the discriminatory trend. In 2000, the Penal Code Amendment (Gender References) Act changed the relevant sections of the Penal Code to refer to “any person” instead of ‘any male” so that lesbian acts were criminalised as well, bringing a dangerous equality to the law for women. The Act also extended criminalisation to heterosexuals by outlawing oral and anal sex regardless of sexual orientation.

In 2000s, visitors from the USA served to stir up the climate of hate. The extremist evangelical minister Scott Lively first visited Uganda in 2002 to drum up homophobia amongst influential Ugandan religious leaders. Then, in 2009, he headlined an anti-gay conference and worked with Ugandan MPs to devise legislation to target the LGBTQI+ community and drum up public support for it. Subsequently, Ugandan MP David Bahati introduced a harsh anti-homosexuality bill which would initiate the death penalty for gay sex, ban LGBTQI+ groups, and force families to report gay relatives.

Yet whilst the 2000s saw more outside influence promoting hatred in Uganda, it also saw the burgeoning and strengthening of a courageous LGBTQI+ activism. The first Lesbian Bisexual and Queer organisation, FARUG, was formed by Kasha Nabagesera in 2013, and in 2004 Sexual Minorities Uganda (SMUG) was formed as an umbrella organisation for the growing movement. So when the Uganda Anti-homosexuality Act was passed in 2014, the activists came prepared and united. Joining with feminist groups, and successfully petitioning the Constitutional Court of Uganda on 1 August 2014, the Act was ruled invalid. However, despite this success, violence against the LGBTQI+ community in Uganda has increased. Forcibly outed people experience “physical threats, violent attacks, torture, arrest, blackmail,” and there have been cases of ‘corrective rape’ among lesbian women whose families and peers forcibly try to ‘correct’ their sexual orientation.

Given that PN has been subject to gang rape herself, no wonder she is desperate and terrified. How disgusting then, that a country who subjugated another country in the 19th century, introducing the hate filled laws that have put PN in danger in the first place, have, through their immigration laws, committed her once again to ongoing threat.

As part of our current research for the Equality & Justice Alliance into LGBTQI+ and women’s movements, Justice Studio has been intimately aware of the extreme abuse and discrimination faced by LGBTQI+ people and activists in Uganda. We strive to understand, and acknowledge, the legacy of colonialism in our work, especially when we are operating in a different country from our own. As we undertake our work in Uganda, we remain cognisant of the privilege it is to work with the Ugandan people, despite what our country of incorporation has inflicted upon them.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks